Table of Contents (Click to show/hide)

Closing the gaps between indigenous and non-indigenous communities

About 120,000 Indigenous people live in approximately 1,200 discrete communities on the Indigenous estate in remote Australia. With historical and geographic issues, the social-economic gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities has been a growing matter of contention. The average education and business growth level of the Indigenous community, in particular, is significantly lower than the non-Indigenous community. Media, policy and economy strategists are putting more attention on this unbalanced development and seeking solutions to close the gap.

In Indigenous Economic Development Strategy 2011-18 (2019), Australia has implemented several policy frameworks to accommodate these issues and made significant progress in education and business growth. There are several arguments in closing the gap in business and education that have strong supporting evidence. In this response, the critical issues in education and business contexts are identified, and those measures adopted to shorten the gap are analysed. The response will focus on the indicators that illustrate progress to show that while significant achievement has been made in education and business growth for Indigenous people – the gap is shorter than it was. There is still a noticeable socio-economic distance that impacts Indigenous life and prospects for advancement.

The dark chapter in Aboriginal history from European settlement in Australia triggered social-economic distance between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities (Alford & Muir 2004). The European invasion and maceration to Indigenous people in 1788 destroyed a peaceful lifestyle and left Indigenous people lost to their homeland along with their wealth, culture inheritance and health. More than 200 years later, amendments were made recognising this disparity when the Australia government officially announced its culture-diversity policy in 1980 along with the acknowledgement from the Australian High Court for initial residency and occupation of Indigenous people in 1992 (terra nullius, Mabo v Cth, 1992 175 CLR). Although a momentous decision for Indigenous people to regain their basic community rights, long-term discrimination has led to a significant disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities in economy, culture, education and household (see Figure 1).

(Figure 2 Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Economic difference, Source: Zhao, Vemuri & Arya, 2016)

Business and education

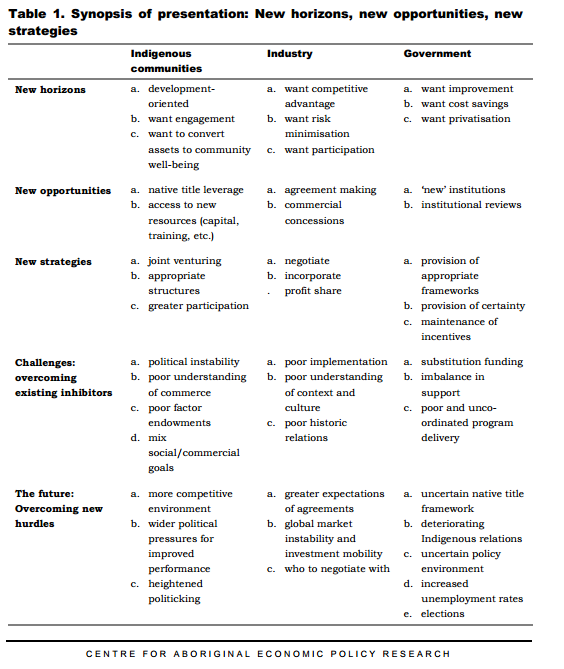

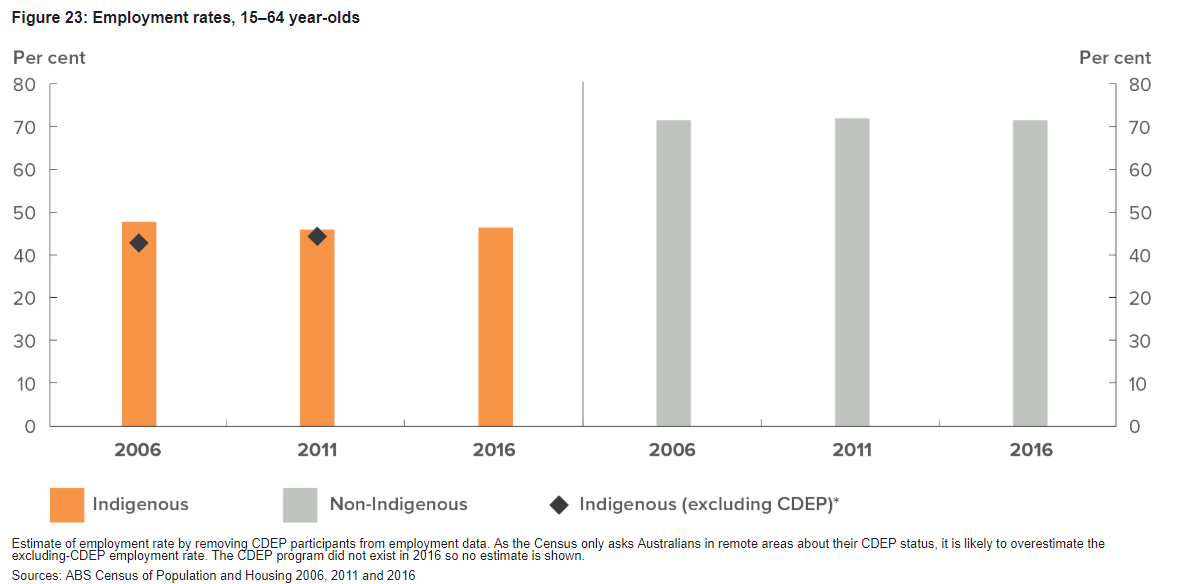

Over these years, critical issues in business and education from a colonial viewpoint barred progression in the Indigenous community, or even having a voice heard in the debate (Alford & Muir 2004). According to Altman (2006), the increased dependence on welfare payments and high unemployment rates are primary reasons behind poverty in Indigenous households (Figure 2). Low education level and the reconstruction of the Australian economy starting in the 1990s also led to a significant job loss in a low-skilled Indigenous population (Biddle 2011). With no steady income, the accumulated effects of poverty and insufficient education weaken the resistance to a colonial-based social arrangement (Alford & Muir 2004).

The constant internal financial crisis and the pressure of disparity cause unpleasant and unstable psychological status in Indigenous individuals, which is a lethal position for entrepreneurship to take place and manage business growth (Foley 2003). Education training is a determining factor for economic development participation ("Indigenous economic development strategy 2011–2018" 2019). The chronic problem of family alcoholism and physical illnesses also affect both attendance and attitudes towards education and school (Welch 1988; Alford & Muir 2004) (Appendix 1). Fewer financial and cultural supports had been provided by the government for Indigenous communities in education and business (Altman 2019). Moreover, due to the intercultural background and remote-location access, past colonial-based education models and business programs are not always suitable for Indigenous people to meet the vocational needs in a hybrid economy (Altman & Fogarty 2010; Altman 2019). All these factors led to a relatively lower qualification rate in Indigenous communities to meet both job requirements and needs of the business, promoting the gap between communities in these two areas.

Education

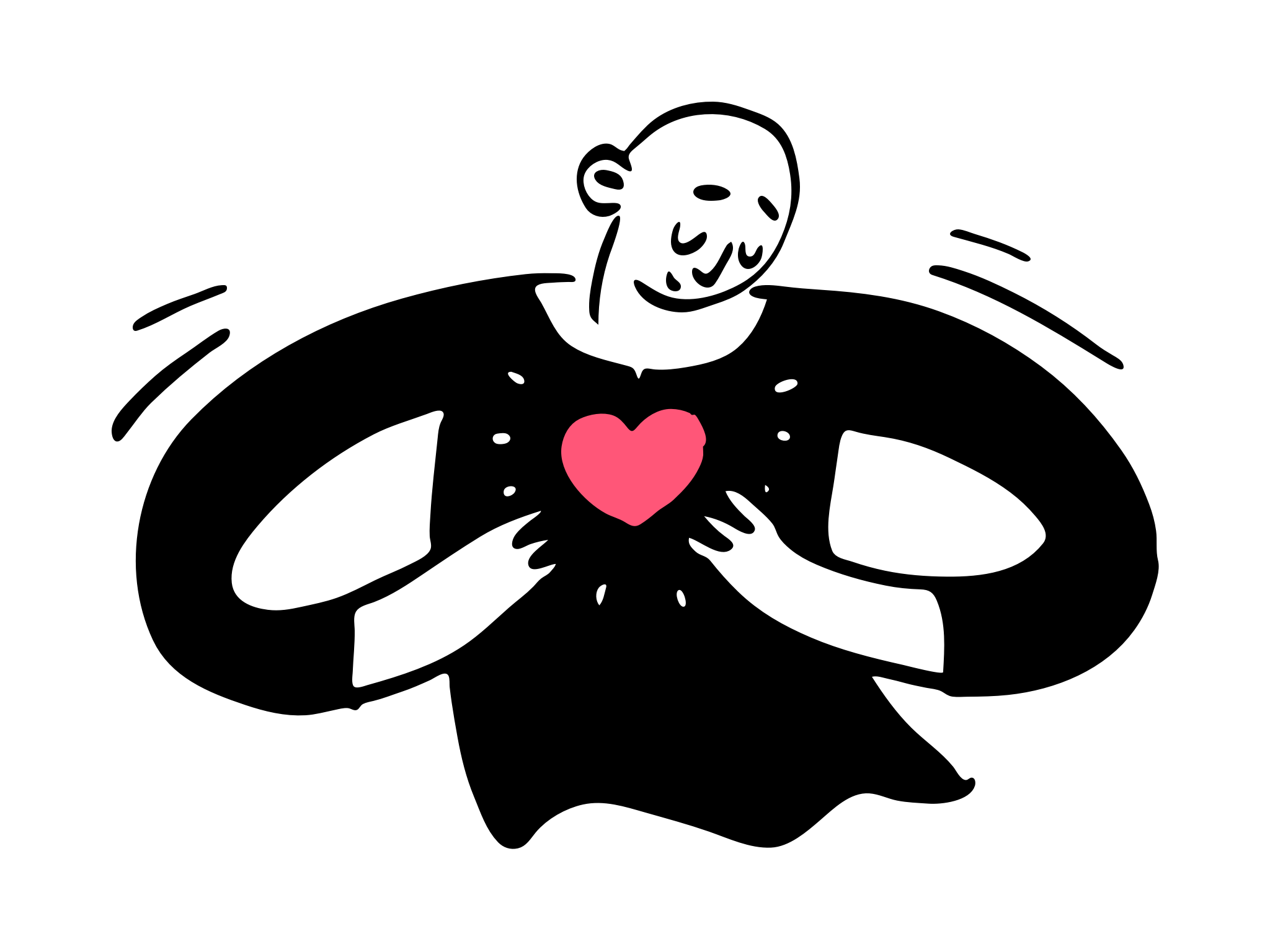

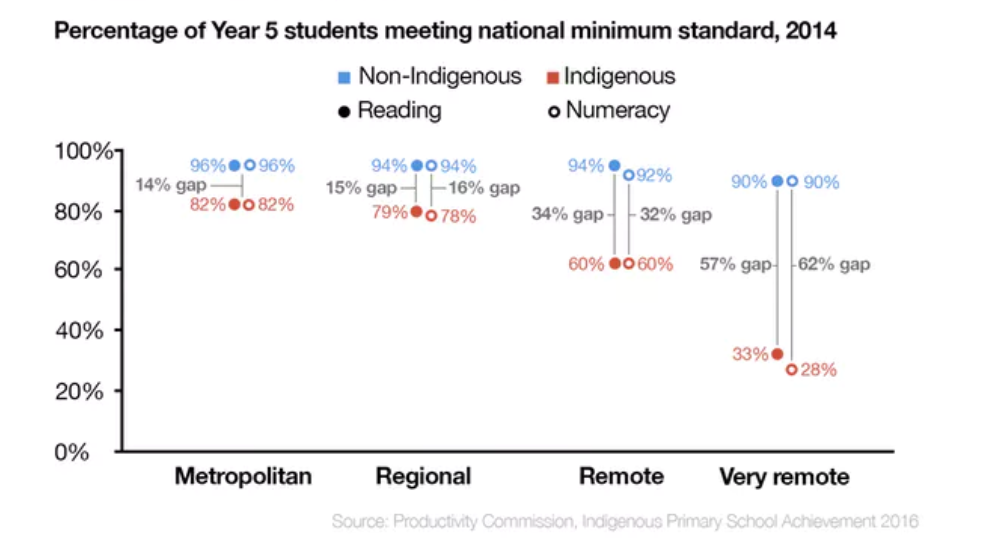

Indigenous Australians perform worse in most social-economic indicators (Biddle 2011). The current policy framework and development strategies by the authorities are assisting in closing the gap (Figure 3). Health, education and employment are associated with both life satisfaction and emotional well-being (Clark, Frijters & Shields 2008). Four out of Six "Closing the Gap" targets endorsed by the Council of Australian Governments include access to early childhood education, literacy achievement for children, Year 12 attainment and employment outcome; and are focusing on education and business improvement (Biddle 2011).

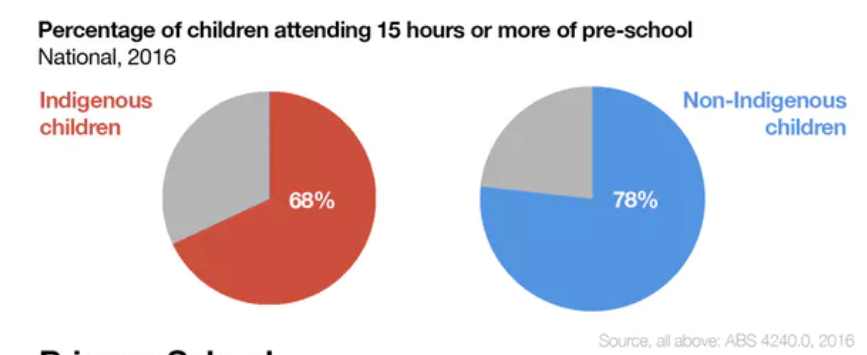

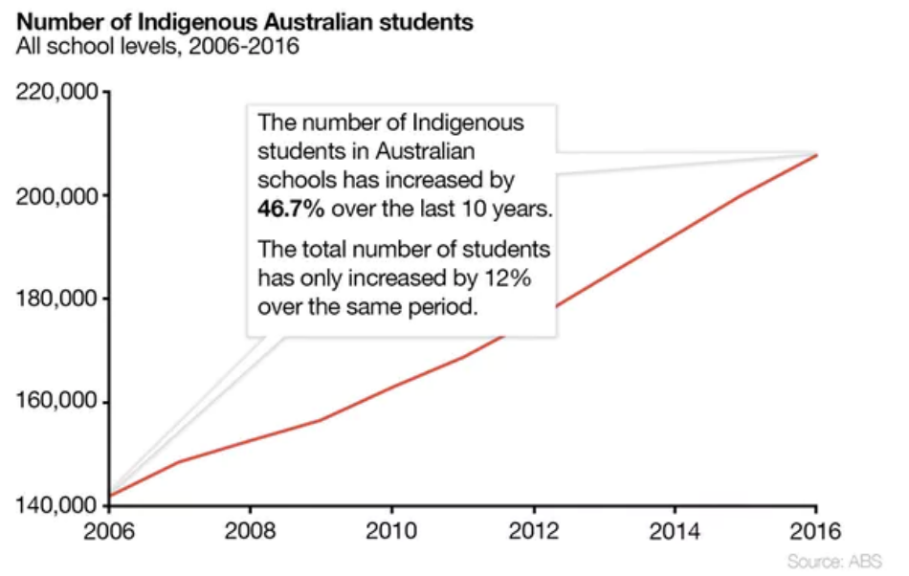

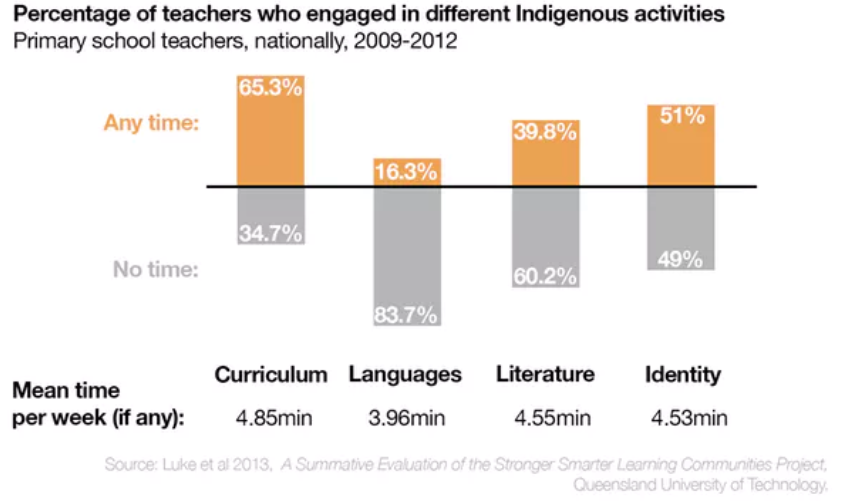

The government improves school readiness and attendance by improving teaching resources and the learning environment ("Indigenous economic development strategy 2011–2018", 2019). While pre-school performance gap remains (Figure 4), the number of Indigenous students in Australian schools has increased by 46.7%. In comparison, the total number of students has only increased by 12% (Shaw, Mountain & Haddou 2019). In the Year 3 National Australian Program in Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN), there is more than double the amount of improvement in Indigenous results (8.7%) compared to non-Indigenous students (4.2%) since the plan started in 2008 (Figure 5) (Shaw, Mountain & Haddou 2019). However, the average gap across all NAPLAN markers is still 17.9%, which indicates an unsolved outcome and persisting discrimination compared to non-Indigenous students (Shaw, Mountain & Haddou 2019; Ford 2013). The remaining NAPLAN gap indicates the need for tailor-curriculum and the literacy teaching method change within teachers for Indigenous students (Thompson & Cook 2012 ; Wigglesworth, Simpson & Loakes 2011) (Appendix 2).

However, this progress (see Figure 5) illustrates proven benefits to closing the gap on business and education including reducing the institutional racism and inequality concerning under-achievement in Indigenous student (Altman & Fogarty 2019). Moreover, adopted policies have been proven to accommodate the special needs for the education program that leads to better performance - the strategy is on the right track.

(Figure 5 Education Progress in NAPLAN 2008-2016, Source: Shaw, Mountain & Haddou 2019)

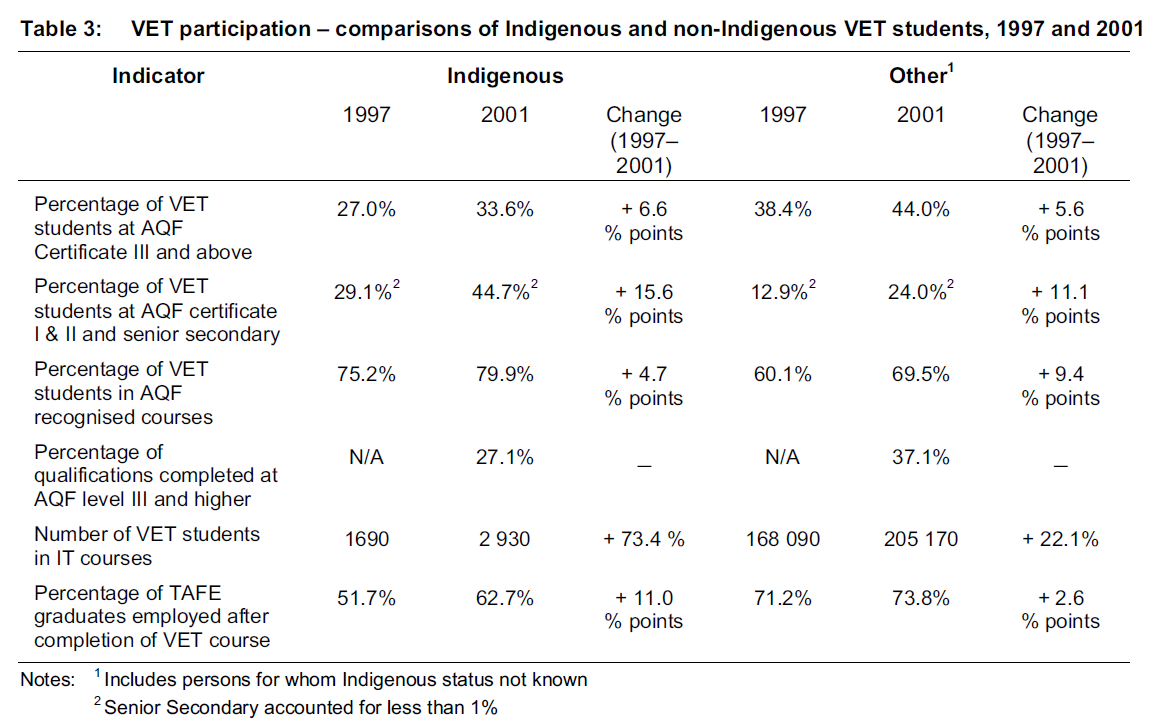

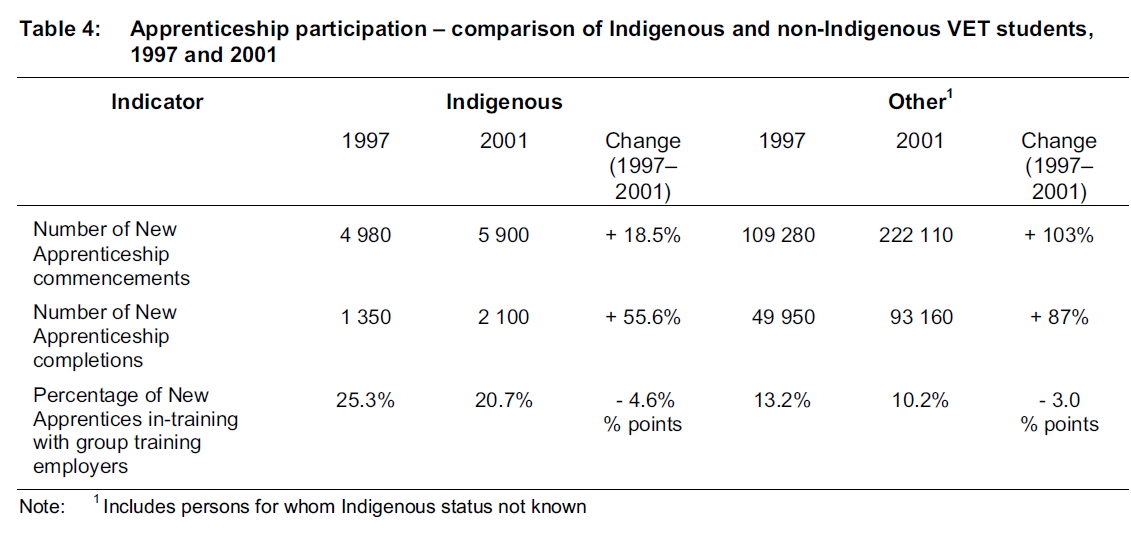

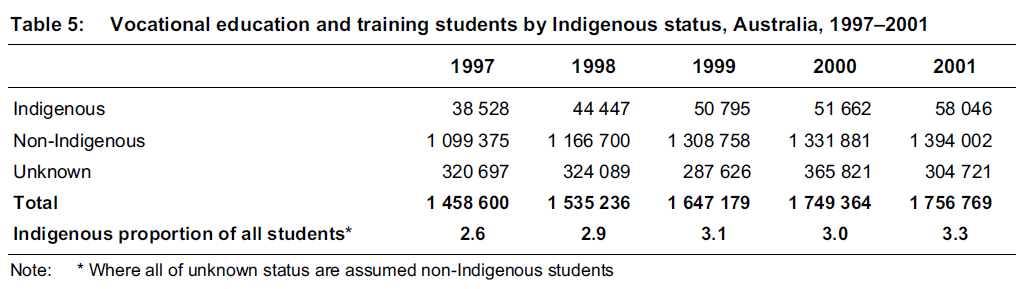

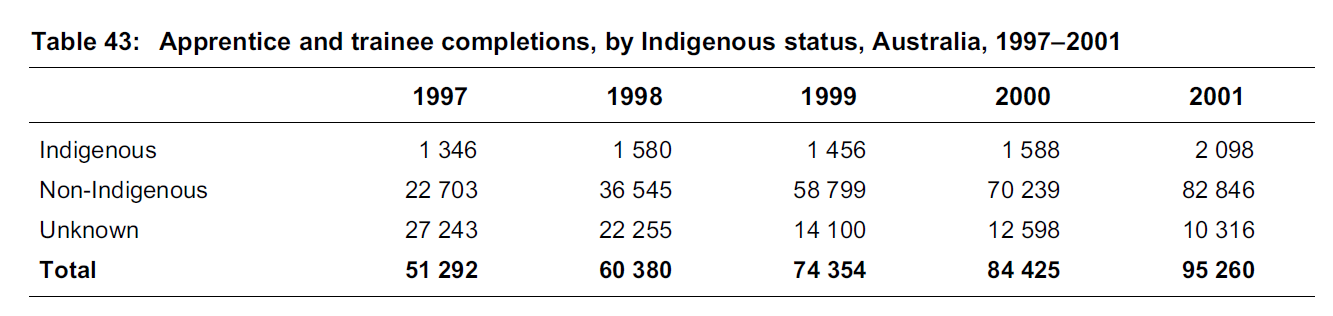

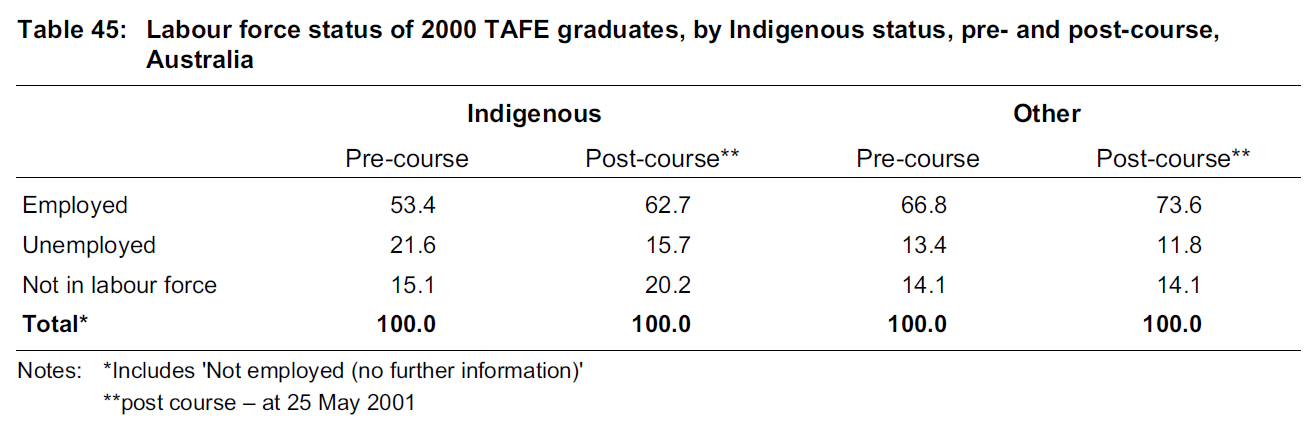

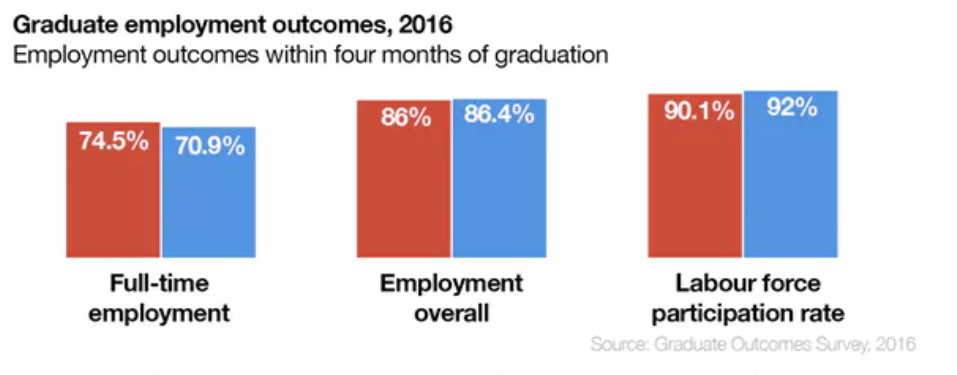

Vocational training and higher education represent better developments for industries and encourage economic participation ("Indigenous economic development strategy 2011–2018", 2019). Multiplying the education fund and tailoring learning programs to financially and emotionally support Indigenous students has also improved the situation (Figure 6). In the past ten years, 21.9% of Indigenous Australians participated in government-funded vocational education training (VET), well over twice the participation rate of non-Indigenous Australians (Saunders et al. 2019). There is a 25% proportional increase in university degree participation, however, graduation outcomes for Indigenous students were significantly worse (Figure 7). This result suggests that educational approaches will need to consider more particular local needs and aspirations in supporting Indigenous students' degree completion (Altman & Fogarty 2019)(Appendix 3).

(Figure 7 Graduation Outcomes for Indigenous Students Were Poor, Source: Saunders et al. 2019; Shaw, Mountain & Haddou 2019)

The Business Development

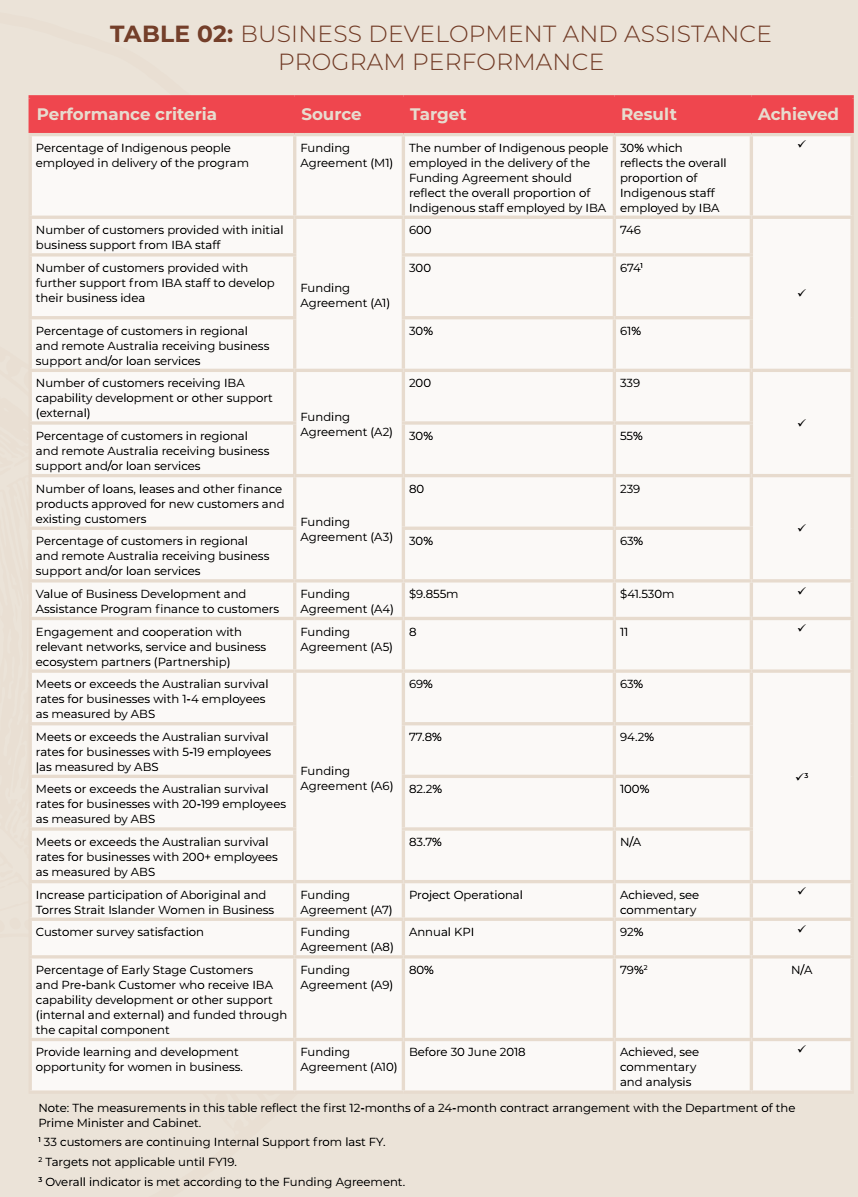

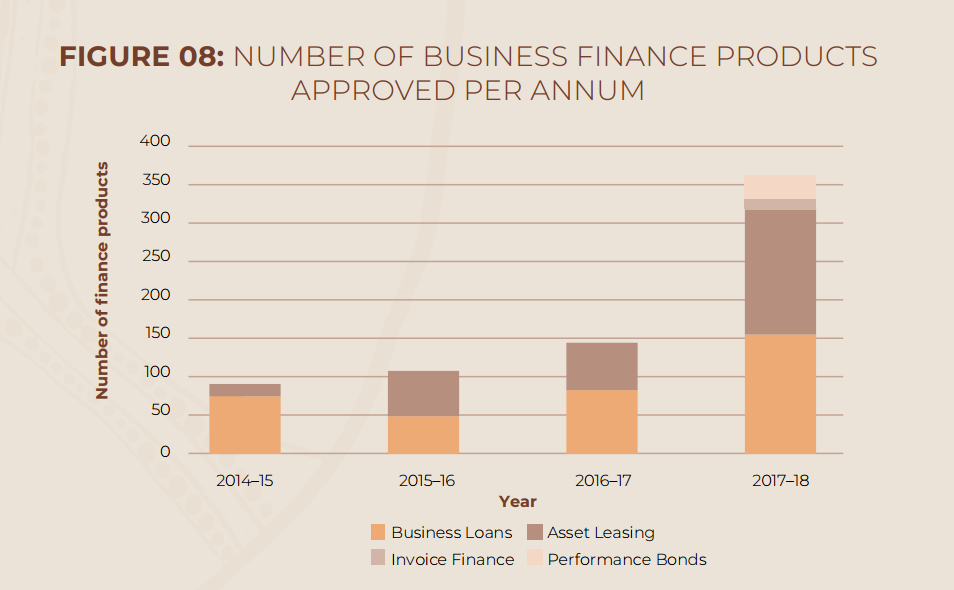

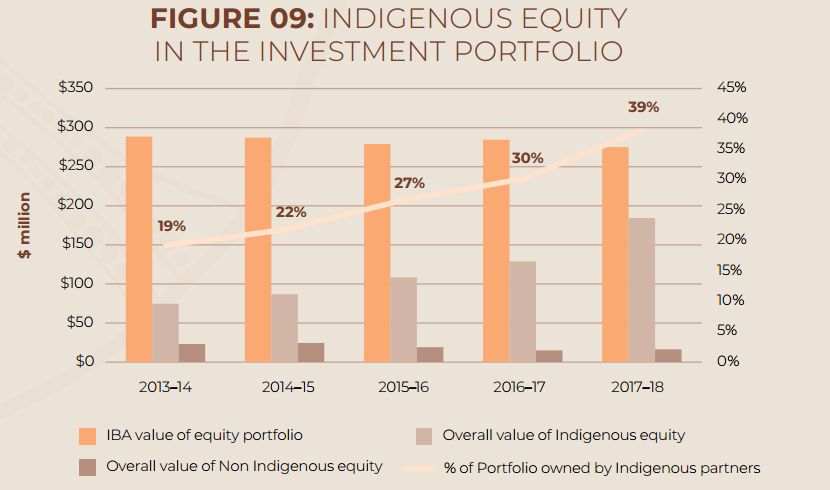

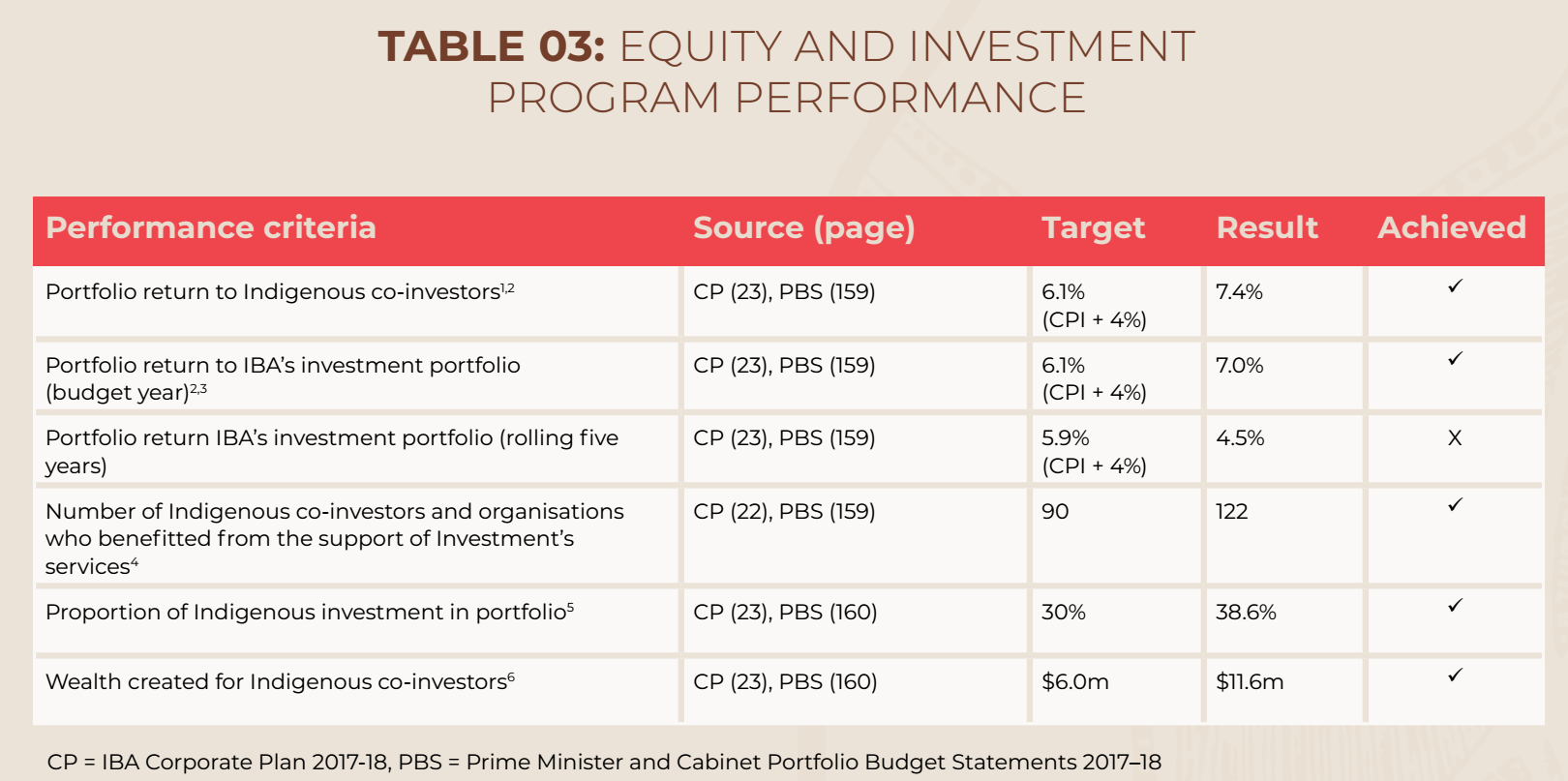

The success in Indigenous business remains unclear as insufficient information and benchmarks were provided in public (Altman 2019). However, improvement in employment supporting business growth was witnessed in the past decades ("Indigenous economic development strategy 2011–2018", 2019; Altman 2019). The government is trying to support Indigenous business growth by offering consultation, clear barriers to access financial support, encourage private-sector partnership and increase government spending in Indigenous business (see Figure 3). Support for Indigenous businesses is focusing on developing sustainable and successful enterprises. The results in 2017-2018 are inspiring compared to the set targets (Figure 8). 55% of IBA customers were approved for financial products (342 customers), and 63% of remote-located small-to-medium businesses were receiving business support (746 customers). A near- perfect survival rate (94.2% and 100%) in businesses and the amount of provided support far exceeded the target indicators (around 20%). Meanwhile,$49.3m was invested and financial injection from the IBA and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander co-investors achieved a positive result as 5 out of 6 targets were achieved (Figure 9). The increasing profitability and financial flexibility in Indigenous business generate an incremental return for the government and private investors spend.

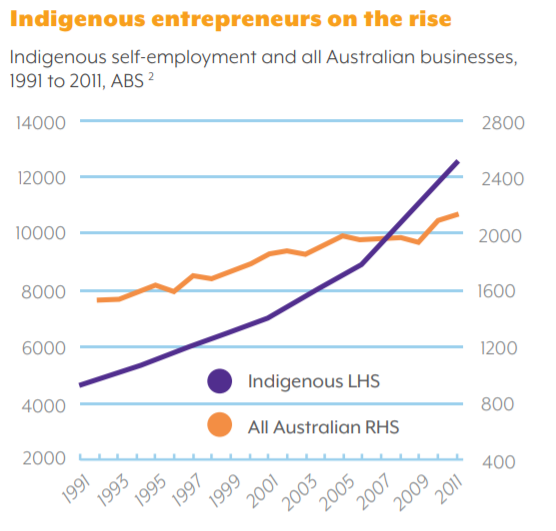

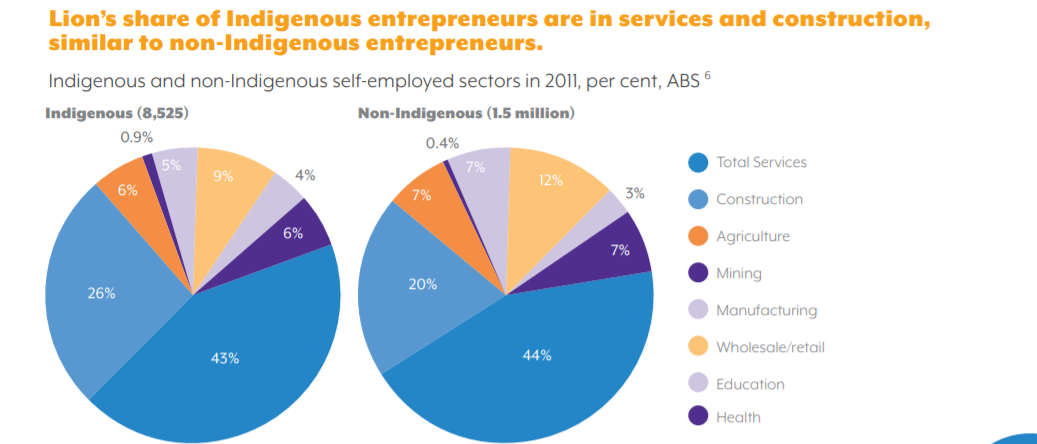

Indigenous graduate employment outcomes turn out to be consistent with non-Indigenous level (Figure 10). However, the overall employment gap remains, and promising growths are yet to be seen. According to the Indigenous Business Sector Strategy (2019), Indigenous entrepreneur numbers are closer to the overall Australian businesses, with Indigenous entrepreneurs much more substantial in services and construction business (Figure 11). Overall, Indigenous businesses and entrepreneurship are growing.

Conclusion

It is shown from this data analysis that the Australian government and economic and social scholars are continually looking for solutions to optimise strategies to shorten the social-economic gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. While progress in education and business growth are significant in the short term, and Indigenous well-being is improving as a whole, but there is a way to go in employment prospects and training. More customised policies are still required to boost Indigenous economy growth in the medium term. This gap in community well-being between colonial and indigenous settlers will be a long-term challenge to Australia's economic and social future.

References:

Alford, K & Muir, J 2004, "Dealing with unfinished Indigenous business: The need for historical reflection", Australian Journal of Public Administration, vol. 63, no. 4, pp. 101-107.

Altman, J 2019, "Indigenous communities and business: Three perspectives, 1998-2000", Hdl.handle.net, viewed May 21 2019, <http://hdl.handle.net/1885/40154>.

Altman, J & Fogarty, W 2019, "Indigenous Australians as 'No Gaps' subjects: education and development in remote Indigenous Australia", Hdl.handle.net, viewed May 20 2019, <http://hdl.handle.net/1885/9738>.

Altman, J. and Fogarty, W., 2010. Indigenous Australians as' No Gaps' subjects: education and development in remote Indigenous Australia. In Closing the gap in education: Improving outcomes in southern world societies. Monash University Publishing.

Altman, J 2006, The Future of Indigenous Australia: Is there a path beyond the free market or welfare dependency? Arena Magazine, Sydney, viewed May 18 2019, <https://vuws.westernsydney.edu.au/bbcswebdav/pid-4381777-dt-content-rid-30346555_1/courses/200425_2019_q2/Altman_Future.pdf>

Biddle, N., 2011. Measures of Indigenous well-being and their determinants across the life course. Income, Work and Indigenous Livelihoods.

Clark, A, Frijters, P & Shields, M 2008, Relative Income, Happiness, and Utility: An Explanation for the Easterlin Paradox and Other Puzzles, Journal of Economic Literature, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 95-144.

Foley, D 2003, 'An Examination of Indigenous Australian Entrepreneurs', Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 133–151, viewed 18 May 2019, <http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.uws.edu.au/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=11605041&site=ehost-live&scope=site>

"Indigenous economic development strategy 2011–2018" 2019, viewed May 18 2019, <https://apo.org.au/node/27022>.

Indigenous groups hoping for 'full partnership' on Closing the Gap strategy 2019, viewed May 22 2019, <https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/nitv-news/article/2019/02/14/close-gap-aboriginal-australia>.

Saunders, J, Jones, M, Bowman, K, Loveder, P & Brooks, L 2019, Indigenous people in vocational education and training: A statistical review of progress, Ncver.edu.au, viewed May 20 2019, <https://ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/publications/all-publications/Indigenous-people-in-vocational-education-and-training-a-statistical-review-of-progress>.

Shaw, C, Mountain, W & Haddou, J 2019, "Infographic: Are we making progress on Indigenous education?", The Conversation, viewed May 19 2019, <https://theconversation.com/infographic-are-we-making-progress-on-Indigenous-education-78253>.

Thompson, G & Cook, I 2012, "Manipulating the data: teaching and NAPLAN in the control society", Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 129-142.

The Indigenous Business Sector Strategy 2019, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, viewed May 25 2019, <https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/ibss_strategy.pdf>.

Wigglesworth, G, Simpson, J & Loakes, D 2011, "Naplan language assessments for Indigenous children in remote communities", Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 320-343.

Welch, A 1988, Aboriginal Education as Internal Colonialism: the schooling of an Indigenous minority in Australia, Comparative Education, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 203-215.

Zhao, Y, Vemuri, S & Arya, D 2016, "The economic benefits of eliminating Indigenous health inequality in the Northern Territory", The Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 205, no. 6, pp. 266-269.

Appendix

The Appendix will introduce figures that demonstrate the reasons behind the critical issues in Indigenous and the potential improvement from the poor performance. It will mainly focus on Indigenous physical health issue, teaching issue in NAPLAN and the participation status in adult education.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Indigenous students start performing worse at the very beginning – participation. Although the number of enrolling in VET is gradually increasing, and the positive change in participation is well-perform to the non-Indigenous students, the percentage of participation still illustrates a big gap, which will have a considerable impact on completion.